It joins a list of thirty other biographies that Sweeney has written since the year 2000 (having edited another eleven books over this same period). Its title is a kind of homage to the more scholarly and in-depth biography of Nicholas Black Elk: Medicine Man, Missionary, Mystic(2009). Instead, the author draws upon secondary sources which convey a sense of the holy man's religious identity.

#Black elk speaks brown professional

As a result, this work does not offer the perspective of a professional theologian, historian, or anthropologist. Church-goers are, then, the target audience for this book that recounts the above history associated with this praiseworthy Lakota Catholic.Īuthor Jon Sweeney has parlayed a non-academic background into a successful publishing career.

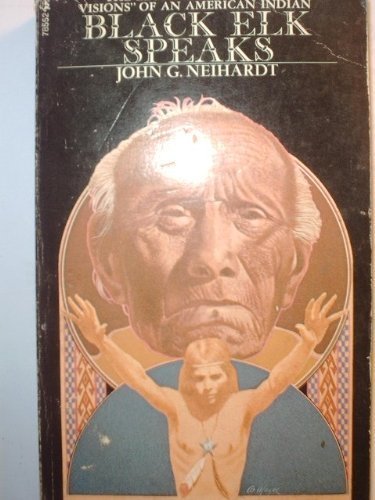

In 2017, the Catholic Church declared that Black Elk was a "Servant of God" (the first stage of the canonization process). Or, as this work addresses, he was a sincere Catholic whose vision of the resurrected Christ inspired him until his death in 1950. Namely, he was a resolute traditionalist who feigned a Catholic practice in order to survive the heartbreaking challenges of reservation life. This revelation spawned contentious debate with commentators espousing one of two positions. He embodied stereotypes associated with the "noble savage"-an inspirational figure thought to be one with nature and having a wisdom known only to Native peoples who were still aware of spiritual realities that mainstream religion was struggling to communicate.īlack Elk: Holy Man of the Oglala (1993) surprised the religious world when it revealed that Black Elk was known among his people as a devout, Catholic catechist. Both works languished on bookshelves until the 1970s when cultural trends propelled Black Elk's image into a mystical stratosphere. Joseph Epes Brown fleshed out the portrait with The Sacred Pipe in 1953. The Black Elk name first became known through John Neihardt's 1932 portrayal of the holy-man in Black Elk Speaks.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)